The war may be winding down for international forces, but not for Afghans. Across the country, civilian casualties are on the rise and the conflict is far from over. As the summer "fighting season" gets underway and clashes intensify between the government and insurgents, Afghan civilians are bearing the brunt of the violence. What's more, despite more than $100 billion dollars spent in Afghanistan by Western governments, the country is facing a dire shortage of modern medical facilities. Run by an Italian charity, Kabul's Emergency Hospital is one of the few places where wounded victims of war are offered life-saving help. Doctors report seeing a 36% rise in casualties in the first two months of this year alone. War-related admissions at the hospital rose by a staggering 85% since 2010.

These photographs were taken at Kabul's Emergency trauma hospital as well as the ICRC's Kabul rehabilitation centre. These are the faces of war in Afghanistan today.

Prisoners of Tradition, Victims of Abuse

Millions of women turned out to vote in Afghanistan's presidential election and a record 300 appeared on the ballot. While Afghan women have seen many improvements since the fall of the Taliban, across the country many suffer abuses and oppression with little hope for change. Domestic violence, forced marriages and honor killings remain a problem. I met some of the victims and wanted to share their stories:

Displaced Faces: A Photo Essay

An Afghan boy at a camp for Internally Displaced People on the outskirts of Kabul.

In April 2014, I spent time with Afghans who have come to Kabul in order to escape the fighting in their home provinces. Some have arrived in the last several months, while others have called this Internally Displaced Person's Camp home for years. Few believe they'll be able to return anytime soon.

- Lucy Kafanov

This mother was forced to flee when fighting erupted in her village three years ago. The family is safe from air strikes here, but she remains haunted by the war. Two of her young sons died when their home was destroyed in a strike. "In my dream, I am running away from the bombs but my babies are still inside the house," she tells me. "When I come back, I find their bodies. I can’t sleep because of it. None of us can sleep well at night.”

Some families in Afghanistan's IDP camps keep caged pet quails to sell for extra cash. More money can be pocketed by taking bets on quail-fighting bouts.

A group of men play traditional music from Afghanistan's southern Helmand Province. The instrument you see here is called a japoni. The man playing it arrived to this IDP camp in Kabul only three days ago. The Taliban have taken over his village, he said, and it was too dangerous to remain.

Siblings, displaced by war in their native Helmand Province.

A mother and daughter sit inside their bare mud brick home. They were forced to leave all of their possessions behind when fighting erupted in the Sangin District of Helmand Province. With job opportunities scarce in Kabul, their economic situation remains dire.

A young Afghan girl at a camp for Internally Displaced Persons.

A photo of powerful ex-jihadi leader and Afghan presidential candidate Abdul Rasoul Sayyaf hangs on a street corner at an IDP camp on the outskirts of Kabul.

A smile.

A fighting quail sits in its cage on the ground at an IDP camp in Kabul.

Most families fled with just the clothes on their backs. With limited work opportunities, many remain destitute.

A man stands proudly in his courtyard at this IDP camp on the edge of Kabul. In his native Helmand province he had land. Here, just the mud and little else.

A young Afghan girl stares back into my camera.

Aysha Bibi lived through many of Afghanistan's horrors: the Soviet invasion, civil war, and the Taliban. But three years ago she says that an air strike nearly wiped out her entire family. Three generations, under one roof, now gone.

Brothers.

Village elder.

A group of Afghans stand on the street of this camp for internally displaced people.

Mahmoud Jawazi is a musician from Helmand Province who arrived to this IDP camp in Kabul three days ago. "Taliban control our village now," he tells me. "The Taliban use our houses as their military bases and the government has no control in our area. What choice did we have? Either leave or die."

A young girl plays the tambourine on the narrow street of the IDP camp.

An Afghan boy, displaced by war.

Slain in a Taliban attack: The story of Hanifa Saadat

One week before Afghanistan's Presidential Election, my team and I were filming at a police checkpoint when a suicide blast went off nearby. The Taliban had staged an attack against a Kabul guesthouse used by Afghans and foreigners. By the time we arrived to the scene, the insurgents were holed up inside and a gunfight was underway.

Maryam Saadat holds a photograph of herself and Hanifa. PHOTO BY LUCY KAFANOV

It could have been a much bloodier day. The insurgents apparently thought they were attacking an unprotected daycare center run by Western families. They got the wrong house. But there were casualties. Officials said that an Afghan child was killed in the attack, apparently a mere passerby. It took some work, but we were able to locate the family of the victim. They were kind enough to let us into their home and to share their story.

Hanifa Saadat was no child. She was a talented, passionate young woman who cared deeply about the welfare of others. She was getting ready to graduate from school to become a doctor. In her spare time, Hanifa worked with the IEC. She was too young to vote in the last election, but this time she was determined to make her mark.

Eight days before the vote, Hanifa finished her shift at the election office. Her older brother was waiting to escort her back home. It was a crisp and sunny day. They were crossing a quiet street in the Karte-Char neighborhood of Kabul when the explosion hit.

Hanifa died because she was in the wrong place at the wrong time -- another innocent victim, caught in the crossfire of a war that wasn't hers. This is her story:

A series of reports from Afghanistan ... coming soon

Now comes the hard part: going through more than 30 tapes worth of material to try to assemble some of the stories I've been able to gather from the past few weeks in Afghanistan. I'll be posting them soon, but in the meanwhile RT's created this (rather overly dramatic) promo video for the series. What do you think?

Amid the forgotten

In Afghanistan, the invaders are often remembered by the things they leave behind. A surreal sight in Bagram: an Afghan boy who makes a living selling scrap stands in front of a 9/11 "Never Forget" sign at the entrance of a junkyard where U.S. military gear is sold as scrap,

Taliban Militants attack Afghan election commission in Kabul

A war without end

I'll be reporting from Afghanistan for the next few weeks. The elections are right around the corner, but in some parts of the country people have more pressing concerns. I met this woman and her daughter at an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp on the outskirts of Kabul. She was forced to flee her home in Helmand province due to heavy fighting between the Taliban and NATO-led forces. The winters are cold here, and money is tight. She burns scavenged scraps of cardboard to stay warm.

I hope to post more in the coming days. Stay tuned.

Meanwhile, a few more photographs can be found here.

German villages face the bulldozer

Energiewende. In German, it means the energy transition and reflects the country's push to generate 80 percent of its power from renewable sources by 2050. Germany feels like a green place. In the countryside, giant wind turbines share the space with idyllic farms; solar panels are easy to find on the rooftops of even the most historic villages. Yet ironically, as Germany embarks on its “green” energy transformation, it has also seen a sudden revival of coal. Atterwasch is one of three villages in East-German Lausitz-region that could soon be razed in order to accommodate the planned expansion of a giant coal mine. Demand for brown coal - or lignite - has been growing steadily, in part due to chancellor Angela Merkel's decision, in 2011, to phase out the use of nuclear power within a decade. The residents of Atterwasch, as you might imagine, are less than thrilled about the whole situation. Here's my story on their fight to keep their homes and way of life.

Cameraman Executed in Syria: An Appeal for Help

It was a senseless death, brutal and unexpected. An Iraqi cameraman tragically killed while on assignment in northern Syria. The exact circumstances are murky, but the reality his death is not: At the age of 35, Yasser Faysal Al-Joumaili is gone. He leaves behind a wife and three beautiful young children -- two daughters and one son.

I had the honor of working closely with Yasser Faisal on a reporting trip to Iraq earlier this year. He was my cameraman. It’s a label that I’ve clung to tightly in his passing, as if that possessive determiner -- “my” cameraman -- could somehow keep him here just a bit longer. But it’s a selfish urge and one that doesn’t reflect reality. Yasser was a freelancer who’s worked with a wide number of journalists, filming for Reuters, Al Jazeera, CNN and countless others.

You may not have not known Yasser, but you have probably seen Iraq through his eyes. His pictures documented some of the most dangerous moments of that decade-long war. Yasser was courageous, talented, passionate and kind. He was always quick with a joke and generous with his smile. He was special, and it hurts to have him suddenly ripped from our lives.

As a freelancer, Yasser lacked the stability of a full-time job as well as the safety net that could have been provided by a major news organization. While there is nothing we can do to bring Yasser back, we can try to ease the financial burden for his family. Some of us have set up a fund to try and do just that. Please contribute if you can. Any amount will go a long way.

http://www.youcaring.com/other/help-the-family-of-yasser-faisal-al-joumaili/116106

FURTHER READING:

Jihadi group kills Iraqi cameraman in northern Syria http://tinyurl.com/n4cgmdq

The dashing Yasser - Al Jazeera Blogs http://tinyurl.com/lvg3skt

Adieu, Yasser Faisal al-Joumaili http://tinyurl.com/lrxeqk8

The Tragic Death of an Iraqi Cameraman in Syria http://tinyurl.com/k2q8rxy

Is Yemen Chewing Itself Dry?

Digging at the Root of Yemen's Water Crisis

By: Lucy Kafanov | Dec. 03, 2012

SANAA, YEMEN — Crippling poverty, widespread government corruption and a growing Al Qaeda insurgency -- Yemen is a country that seems to have no shortage of problems. But add this one to the list: a shortage of water could soon make Sanaa the first world capital to run dry.

"It's a catastrophe," says Dr. Ismail al-Janad, the former Chairman of Yemen's Geological Survey and Mineral Resources Authority. "We have limited water resources and bad management of those resources. If we continue like this, within ten years the water will run out in Sanaa as well as other areas."

The problem is deceptively simple: too many people, and not enough water to go around. The number of Yemenis has quadrupled in the last half century, and is expected to triple again in the next 40 years, to about 60 million. Across the country -- and especially in the capital of Sanaa -- water is used up faster than can be replenished by annual rainfall. Those who can afford it get their water delivered by trucks. The rest have to make do however they can. There are public taps, but water pollution and shortages are a problem.

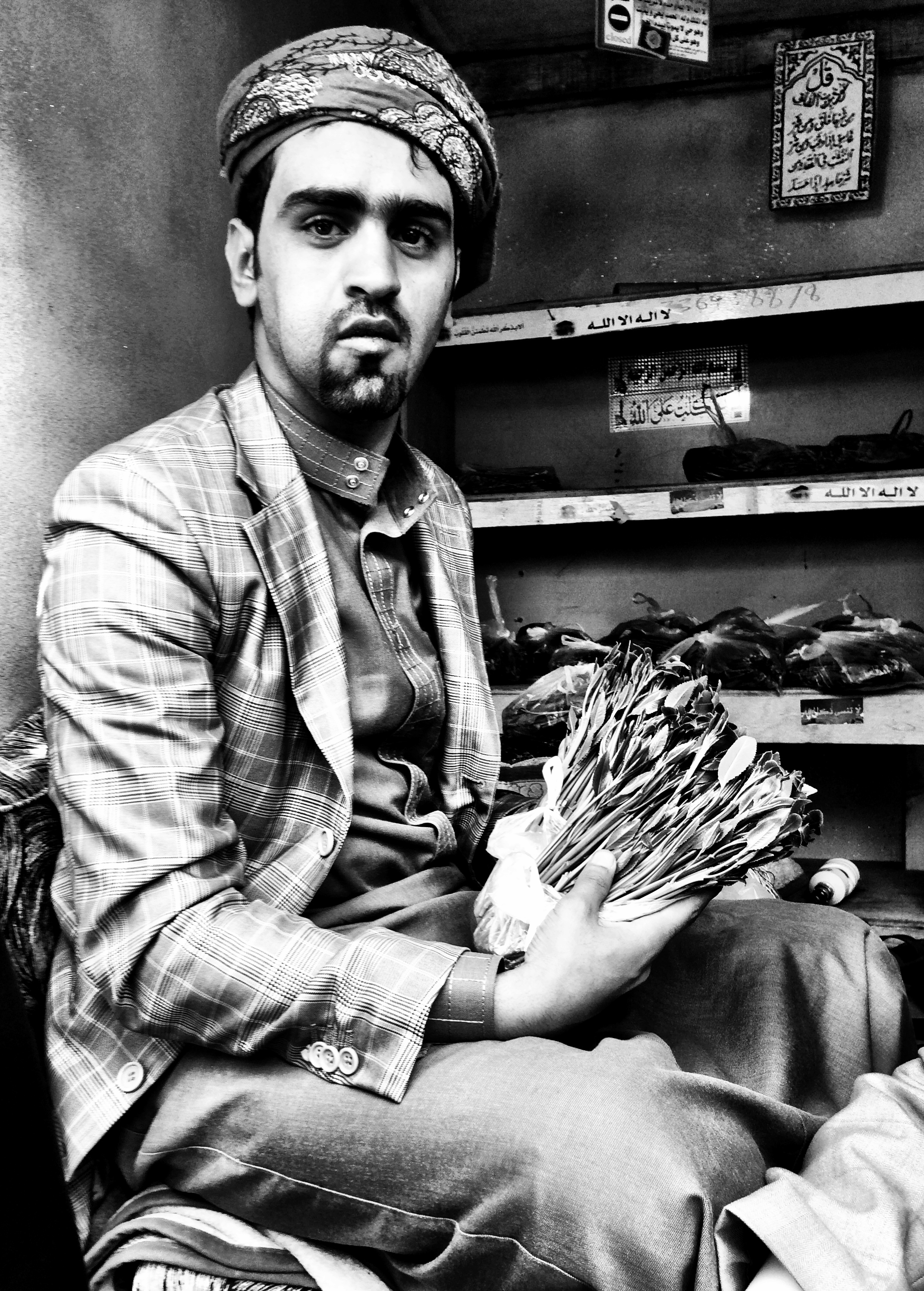

A Qat seller in Sanaa. Photo by: Lucy Kafanov

And with a reliable supply of clean water priced out of reach for many residents, political analyst Abdul-Ghani Al-Iryani says that for some segments of the population, the water is as good as gone. "We shouldn't be talking about Sanaa running out of water in ten years, it has actually run out of water," he said. "It's a matter of definitions now -- and that's not just Sanaa, it's the entire country."

At an altitude of 7,500 feet, Sanaa is one of the highest capital cities in the world. Some of its wells are more than 4,000 feet deep but many are no longer usable because of the sinking water table.

While population growth and poor management are to blame - there's another culprit: Qat. The leaves contain a mild narcotic and chewing them is a key part of Yemeni culture. Almost everyone does - more than 90 percent of men, according to the World Health Organization.

Like clockwork each afternoon, the narrow lanes of Sanaa's numerous Qat souks fill up with men buying their evening supply. There are endless varieties of the plant, and no shortage of customers. The tradition goes something like this: a huge meal, followed by a gathering at one of Sanaa's countless divans. Men will sit together for hours, chewing, smoking and debating politics. Women will often chew as well, although separately from the men.

Most Yemenis will bristle at the notion of Qat as an addictive drug. Chewing the leaf induces mild euphoria and a state of excitement - not terribly different from drinking several cups of strong espresso. Criticism of Qat-use tends to focus on the resulting drain on household budget, disincentive to the local production of food crops and as an obstacle in economic development. Yet this post isn't about the pros or cons of chewing Qat, but rather one indisputable reality: it takes a lot of water to cultivate the plant. More than half -- perhaps even as much as a third of Yemen's scarce water is used to grow the crop.

A Yemeni Qat seller shows off his wares at a souk in Sanaa. Photograph by Lucy Kafanov

For the farmers, growing Qat often means guaranteed high profits. But for the country, it means a slow and inevitable death, says journalist Maged al-Ariki, who's written a book about Yemen's looming water crisis.

"Without doubt, Yemen is chewing itself to death," Al-Ariki tells me. "Agriculture is using about 93 percent of the extracted water, and most of that goes to Qat. The government is doing little to address the misuse of water and as a result areas will inevitably go dry."

To better understand how farming Qat is affecting the water supply, my cameraman and I drive out to a farming village in Hamdan, on the outskirts of Sanaa. Our "guide" is a local journalist whose uncle owns a farm in the village. As the four-wheel-drive truck rattles it's way up the unpaved mountain roads, the occasional stone houses eventually give way to a vast expanse. We find ourselves staring at what seems to be an utterly inhospitable terrain, but in the midst of it, a sea of green: lush Qat trees stretching across the horizon.

We climbed out of the truck as two men slowly made their way across the rugged terrain to meet us. They are the farmers who own this land. In the distance, a group of young men sat perched on a rooftop, eyeing us warily. One of the farmers waves to them and shouts something in Arabic. The men on the roof seem to relax somewhat. In a small village like this, the presence of foreigners doesn't go unnoticed. And although I felt relatively safe as a guest, the camera is often an unpredictable element.

Amid the rugged landscape in Hamdan, a sea of green Qat trees. Photograph by Lucy Kafanov.

We walk with the farmers into one of the groves. The Qat trees rise a few feet above my head, and dozens of them are planted next to one another in neat long rows. The ground crumbles beneath each step, yellow and cracked. The soil looks parched, save for a few occasional stagnant puddles. The problem with Qat cultivation is supposed to be the massive amount of water it requires, but here amid the arid soil, it certainly doesn't look like this is what's draining Yemen's supply. "Where's the water?" I ask one of the farmer. He smiles and tells me to wait until after lunch. The fields are watered early in the morning and again late in the afternoon. More water means faster growth, they tell me, and that means more cash for the farmers.

"We used to grow grapes, peaches, pomegranates and other fruits, but it simply wasn’t as profitable as Qat," says Muhammad Yahia Sa’ad, who's been farming all his life. "We ended up rooting out the other crops."

Ice-cold water served out a tin can to go along with lunch. Photograph by Lucy Kafanov.

Muhammad invites us to his home to eat. We sit on the ground, sharing flat, freshly-baked bread, and a stew called fatha. Served in a pot blackened by fire, fatha is a thick, meat-studded soup that's brought out piping-hot, covered in green foam. It doesn't look like the most appetizing dish, but is absolutely delicious once you taste it. One of the farmers pours ice-cold fresh water from a clay jar and into a tin cup, which all of us share. After the meal, it's time for the water.

We set out to for one of the wells in order to watch the irrigation process in action. As we drove along the bumpy roads I noticed long, thin pipes zigzagging across the fields. Each connects to a well and allows farmers to irrigate their fields. There were once 30 wells serving the village, but Muhammad tells me ten have already gone dry, and two more were on the verge. I ask him what he'll do once there's no more water.

"Allah will take care of us," he says with a shrug.

For some inexplicable reason, when I heard the word "well" I had come to expect something along the lines of a hole in the ground and a bucket on a rope. Instead, we pulled up to a small brick building. Inside was the mechanism that was responsible for bringing the water to the surface: a giant pump attached to pipes that bore deep into the ground. It was kept under lock and key when not in use, and we had to wait around for a bit for the well-keeper to arrive. Soon enough, a white Toyota SUV came rumbling towards us. With a cigarette dangling out from his lips and right cheek full of Qat, the driver hopped out. Grabbing a canister of diesel fuel out of the truck, he headed inside towards the machine. The cigarette thankfully remained securely in place as several gallons of fuel were poured in. With the turn of a key, the machine roared to life. Somewhere, roughly 400 meters below where we stood, water was rushing up to the surface.

A Qat farmer in Hamdan watches as the water starts flowing. Photograph by Lucy Kafanov.

We step back out into the blinding sun and make our way to a cross-section of pipes. Using a giant red wrench, Muhammad unscrews something on the side and we watch as a trickle of water turns into a gush. The water made its way down a shallow ditch that's been dug out specifically for this purpose. Grabbing the camera, we head after it. After several minutes of walking, the ditch opened up into a massive Qat field. The yellow cracked dirt that so puzzled me earlier was quickly swallowed by the flood. Muhammad was following the flow several feet ahead of us, occasionally using a shovel to help guide the water towards one side or another. Eventually, I kick off my shoes and wade into the field to film a piece to camera. The water came up just past my knees.

Subsidized diesel powers the well's water pumps. Photograph by Lucy Kafanov.

By law, only the government is allowed to dig and maintain wells. But in reality, it's a free for all. That makes it almost impossible to control how much is pumped out. Based on conservative estimates, about 250 million cubic meters of water are extracted from the Sanaa basin every year, 80 percent of which will never be replenished. What's more, massive government fuel subsidies make producing water using the diesel pumps relatively cheap. Easier to drill for more rather than learn how to make do with less.

It wasn't always like this. For centuries, Yemeni farmers captured rainwater for their crops. In some areas, they built dams. But international organizations got involved in the 1960s and 1970s, encouraging Yemen to drill and use underground aquifers instead. The World Bank and International Monetary Fund incentives may have been well intentioned, but ultimately the projects helped drain water tables quicker than anyone expected.

After our shoot, my cameraman and I head back to the truck. The goal is to get back to Sanaa before sunset in order to avoid problems at the checkpoints. As we pack up our gear, Muhammad comes over with two clear plastic bags full of freshly-harvested Qat leaves. A parting gift, he says. We begin our slow and bumpy drive back to Sanaa, while Mohammad and the rest of the men go indoors to start their daily chew. In Yemen, the evenings belong to Qat, and solving the water crisis will simply have to wait another day.

Further Reading:

How Yemen Chewed Itself Dry | Foreign Affairs http://tinyurl.com/k389ob5

Yemen's Water Woes | The Middle East Channel http://tinyurl.com/97gshqz

In Yemen, a drone strike devastates a community

I set out to try to understand how the covert drone war against Al Qaida militants has affected civilian populations in Yemen. Here's my report:

Yemen is one of the focal points of the covert U.S. drone campaign against Al Qaeda militants. But despite President Obama's promise of more transparency, relatively little is known about who is actually being killed. Journalist Lucy Kafanov was able to reach one Yemeni village, where she found a community devastated by a strike.

Mechanics of a Catastrophe: 'A case study in Syria’s hidden war'

Syria. It's a stalemate that is anything but stale: Mired in bloodshed and appalling violence, shifting and evolving daily, yet dragging on seemingly without end.

Countless lives are lost and many more are interrupted. The conflict has resulted in what the UN High Commissioner for Refugees recently described as a "disgraceful humanitarian calamity with suffering and displacement unparalleled in recent history."

It is obvious that war is the cause, but a haunting new report from Roy Gutman and Paul Raymond offers greater insight into why. It documents the Syrian government strategy of decimating areas sympathetic to the opposition with heavy weapons, followed by a brutal "cleansing" by ground forces.

The story looks at this summer's government assault against Ariha, a small rebel-held town south of Idlib, The tragedy that unfolded here is described as a "case study in Syria’s hidden war." From the article:

To “cleanse” the town, government helicopters dumped dozens of “barrel bombs” – improvised explosive devices filled with shrapnel and varying in size from a large pipe to a garbage Dumpster – on houses and shops, multiple witnesses told McClatchy. Tanks and howitzers fired into the town, and the army also fired mortars, gravity bombs, vacuum bombs and cluster bombs.

Outgunned and low on ammunition, the rebels gave up. They and around 70,000 civilians fled to other towns and to Turkey, and that may have been the aim of the operation. The United Nations now estimates that 6.8 million Syrians have been displaced from their homes, and outside experts say the number may be as high as 10 million.

It's a disturbing report and absolutely worth a read. Here's the link:

http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2013/11/11/207990/battle-for-strategic-syrian-town.html

Yemen: In Between Shadows and Light

Filming in Yemen was both a challenging and immensely rewarding experience. Below are some of the images from the trip.

Recognized at the International Media Excellence Awards

This past week brought with it an unexpected surprise: my story examining the impact of drone strikes on civilians in Pakistan was recognized at the 2013 International Media Excellence Awards, which is run by the Association for International Broadcasting.

The winners of the 2013 AIBs were announced this week by the Association for International Broadcasting at a gala dinner at LSO St Luke’s in London. The awards are in their ninth year and celebrate the best in engaging, powerful, moving and innovative reporting.

My piece was shortlisted in the category of short features - competing against stories submitted by CNN, Bloomberg and Voice of America, among others. While CNN took the prize for its "Damascus Undercover: Daraya," my story received a 'highly commended' accolade. It was described as, "upsetting, yet honest and direct."

It was a pleasure to be recognized. My only regret was that my excellent cameraman from Pakistan - Belal Tariq - could not be present with me.

Lucy Kafanov at the 2013 International Media Excellence Awards in London.

test 2

TEST

test post.

Lucy Kafanov, NBC News Foreign Correspondent

Kurdistan: The Other Iraq

Green Fields.

That was my first sight of Iraq as the airplane made its descent onto the runway. It certainly shouldn’t have been a surprising one given the region’s history as the cradle of civilization. But it was the clash, not birth, of civilizations that I had expected to see. After a decade of war, the Iraq I had envisioned was one of sand and dust, rubble and crumbled buildings - not the idyllic red soil and lush green farmland grass that stretched as far as the eye could see.

We had arrived to Erbil, the capital of the semi-autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq's north. As airplane was taxiing towards the terminal I couldn’t help but think that Erbil’s International Airport would not look out of place were it located in a small European city. It was originally built at the beginning of the 1970’s as an Iraqi military base and remained as such until the U.N. Security council established a no-fly zone after the end of the Gulf War in 1991, in order to protect Kurds against Saddam Hussein. Since then, the Kurdish region has thrived, and in some ways the modern-looking airport symbolizes the change of fortune for Iraq’s Kurds.

Some 400 kilometers north of Baghdad, the city of Erbil serves as the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. The region has its own flag, parliament, government, president, armed forces and its own language. It’s been touted as one of the few success stories of the Iraq war, with the Kurds having transformed an impoverished and traumatised society into a thriving one in the years since they gained autonomy in 1991.

The Kurds’ success can in no small part be attributed to an oil-fuelled economic boom, which has attracted a wide variety of international investors. Turkish investment is the most visible. The sleek new terminal in which we were standing was built by a Turkish company. Turkish construction had built much of Erbil, and Turkish companies account for more than half of the foreign businesses there. Nearly 80 percent of local goods in Kurdistan are Turkish (a source of frustration at the end of our trip, when trying to shop for authentic Kurdish souvenirs only to find Turkish imports). And a proposed pipeline through Turkey will soon link oil-rich Iraqi Kurdistan to Western markets. While all this seems to have benefitted the Kurds, it’s also been a source of growing tension between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Baghdad.

For now, the Kurds remain dependent on Baghdad for survival. The region is eligible for 17 percent of Iraq’s national budget, derived mostly from oil exports that are presently controlled by the central government. Money, oil, geography and the constitution keep the country together - although the very same factors threaten to tear it apart.

Whatever the differences between Baghdad and the KRG, we are still in Iraq. The cell phone company adverts lining the corridors of the airport are a testament to this. So are the dark green passports in the hands of nearby travellers: the words “Republic of Iraq” are emblazoned on the dark green covers. Citizens of one country, which feels like two.

“It certainly ain’t like the rest of Iraq,” remarked Tom, an American Embassy official from North Carolina whom we met while waiting for our luggage. Tom told us what we already knew: that Kurdistan was the safest place in Iraq today. He was heading to Baghdad on a private embassy flight, but warned us to avoid going there at all costs without security.

“They don’t much like Westerners there,” he warned, adding: “Of course, they welcome us with open arms here.”

I asked Tom how he deals with that issue when interacting with local Iraqis.

“We don’t really interact with them,” Tom replied. “Safety and security first.”

His words lingered in the air even after a group of embassy workers hurried him away.

The anniversary of that war was what brought us to the country. With our Iraqi visas on hold, mired in a long process of bureaucracy, Kurdistan was the only option for us to arrive in time to cover Iraq ten years after the U.S. invasion of Iraq. For visitors like myself and my Spanish colleague, there was no visa application process, lengthy paperwork or numerous interviews with consular officials. You simply get off the airplane, walk towards immigration control, and hand over your passport to get stamped.

“Welcome to Kurdistan,” said the smiling officer as he reached for my passport and stamped a 10-day KRG visa on one of the empty pages.

“Technically, Iraq, no?” I asked.

The officer blinked for a moment and handed me back my passport. “Welcome to Kurdistan,” he repeated, waving me past.